Original article (in Croatian) was published on 21/11/2023; Author: Petar Vidov

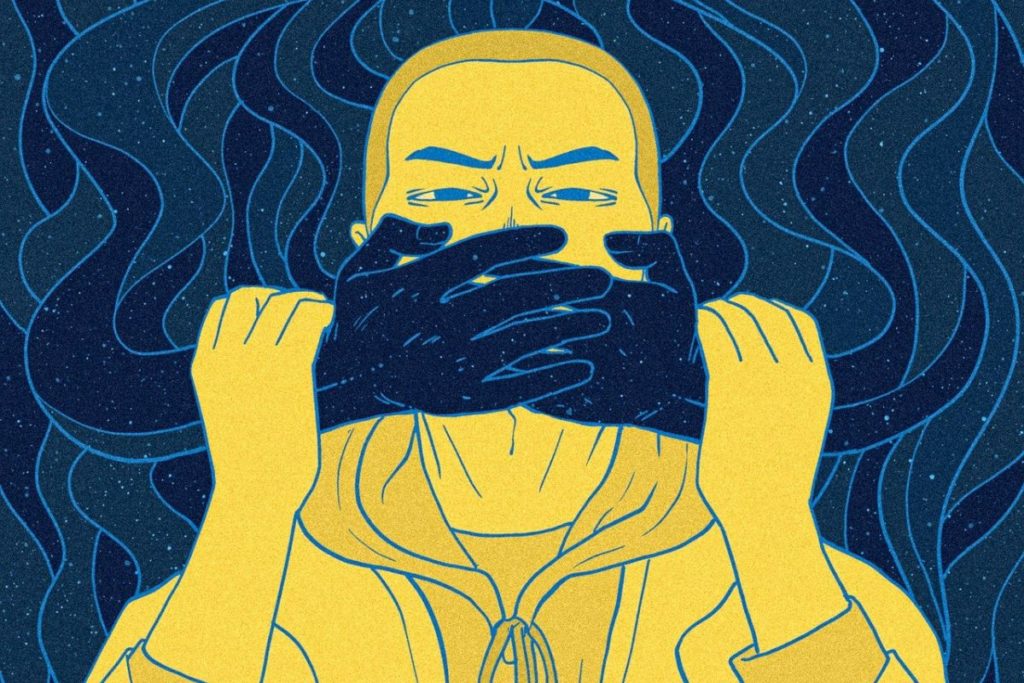

Case studies from Germany, Austria, Spain and Croatia reveal a pattern used by the extreme right in an attempt to intimidate journalists and the media.

Journalists and fact-checkers across Europe are the target of an intimidation campaign that tries to silence them, reveals Faktograf’s research conducted earlier this year as part of the project “Decoding disinformation patterns of European populists”. 41 media organizations engaged in fact-checking participated in the research, and 90 percent of them experienced attacks and threats.

Such findings are supported by case studies from Austria, Germany and Spain, which were conducted as part of the same project by the German daily newspaper Die Tageszeitung and the international organization International Press Institute (IPI). Die Tageszeitung investigated cases from Germany and Austria, and IPI focused on the case of Spain’s Maldita, a media organization that, like Faktograf, specializes in fact-checking and exposing digital disinformation.

The case studies, published on the IPI website, describe the attacks on the German journalist Alexander Roth and the Austrian journalist Franziska Tschinderle, as well as the harassment experienced by the participants of Maldita’s educational project “BuloBús”.

Case studies

The intimidation and harassment experienced by Alexander Roth, a journalist and editor of the regional German daily newspaper Waiblinger Zeitung, is very similar to the attacks experienced by members of the Faktograf editorial staff at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, Roth investigated the activities of anti-vaxxer groups and their connections with the extreme right in Germany, which tried to take advantage of protests against epidemiological measures in that country. Because of his journalistic work, he received threats of violence and death, and a campaign was launched against him on social networks, which made his journalistic work much more difficult. During the coverage of the protest against epidemiological measures in Stuttgart, he was exposed to various insults and pressures with the obvious aim of silencing him and preventing him from further work.

“I don’t take a step without asking myself how safe I am. When I get close to my house, I turn around every few seconds. When I’m out in private, I have all the protest dates in my mind, so I don’t accidentally walk into the protesters”, Roth wrote on X (formerly Twitter), reflecting on his experience.

Members of Maldita’s team, which visited 20 Spanish villages in April and May 2023, were exposed to similar forms of harassment to teach interested citizens how to recognize fake and manipulative claims. Several Twitter user profiles responded with a coordinated campaign of intimidation, as a result of which members of Maldita’s team began receiving insults and threats through digital communication channels. They were met with protests in several villages, inspired by unsubstantiated claims that Maldita was censoring opponents of the Covid-19 vaccination on social networks, which is why the BuloBús itinerary had to be changed. Maldita’s research showed that it was a coordinated campaign, conducted through several anonymous user profiles on Twitter and Telegram, social networks known for not making special efforts to moderate content that is full of hate speech and disinformation.

Austrian weekly journalist Franziska Tschinderle, on the other hand, found herself the target of attacks by Hungarian state media under the control of Viktor Orban’s regime. The hunt that Orban’s media has been conducting against her for days was launched after she sent a few short and simple questions to Fidesz, Orban’s party. Inspired by the March 2021 announcement that Orban, together with the then leaders of the Italian and Polish right-wing Matteo Salvini and Mateusz Morawiecki, would form a new alliance of European right-wingers, Tschinderle sent three questions to Fidesz in which she sought comment on the future political plans of the announced alliance. Instead of answering, she found herself the target of a disinformation campaign conducted through Hungarian media under Orban’s control, which accused her of wanting to sabotage the shared political ambitions of Orban and his allies. After the campaign orchestrated by the Hungarian media, Tschinderle began to receive insults and threats through digital communication channels, which is why the Austrian Minister of Foreign Affairs finally reacted, telling the Hungarian authorities that their behaviour was unacceptable.

A pattern of extremist attacks on journalists

In all the described cases, there is a common pattern that members of the European extreme right use to try to silence and intimidate journalists.

In turn, these are attacks that are encouraged and encouraged by politicians who recognise the opportunity to consolidate the voter base in the Covid-19 pandemic by placing inaccurate, unfounded and manipulative claims or conspiratorial narratives in the public space.

When asked specific questions about their disinformation claims, they respond by avoiding reasoned debate and directing the anger of their supporters at journalists who question their motives and intentions. The goal of such behaviour is to cause fear and discomfort and to discourage future critical questioning of their baseless and manipulative theses. For the same purpose, in some countries, among which Croatia is the leader, the so-called SLAPP lawsuits (i.e. strategic lawsuits against public participation), serve to try to exhaust journalists and the media with lengthy legal proceedings.

The purpose of such tactics of attacking journalists and the media is to provoke a reflex of self-censorship, i.e. an attempt to dissuade journalists from critical reporting, which could later expose them to various inconveniences – from lawsuits to internet harassment characterized by insults, threats and hate speech.

This text is part of the project “Decoding disinformation patterns of European populists” supported by the European Media and Information Fund.