Original article (in Croatian) was published on 02/12/2022

The climate crisis is a social crisis – this was said at the presentation of the first Croatian study on adapting workplaces to rising temperatures. SSSH and FES co-financed the study “Climate and work” as a basis for negotiations on the future of work.

The climate crisis is here, and workers must prepare for it, which is impossible without stronger involvement in negotiations with governments and employers – this is the message from the presentation of the preliminary results of the study “Climate and Work: Adaptations of Workplaces and Workers to the Climate Crisis”, conducted by an economist Ana Maria Borromisa. The first analytical study of this type was presented shortly before the Congress of the Association of Independent Trade Unions of Croatia in Terme Tuhelj as a starting point for a social dialogue in Croatia about the consequences of the climate crisis.

After decades of discussions about the dangers of the climate crisis, and the technologies and investments needed to reduce emissions and increase protection from the inevitable consequences, the people who will live and work in that heated world remained more or less on the sidelines. And moving the mercury on the thermostat upwards will bring not only poverty to many workers in the world but also health problems, while for some of them, it will also mean death.

Social crisis

Unbearable heat will further aggravate all social injustices and, above all, inequality. That is why, as stated by Sonja Schirmbeck from the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, co-financier of the study, the climate crisis should be understood as a social crisis.

One reason is that the deprived part of society contributes less to the crisis but will be more affected. Workers already doing low-paid jobs are unlikely to insure their assets from the consequences of the climate crisis, such as floods and fires. Croatia is at the very top of the EU member states regarding the size of damages from extreme climate events in relation to GDP, and at the very bottom regarding the share of insured damages. While according to the European Environmental Agency, insured losses in Denmark and the Netherlands are 56% and 55%, only 3% of damages are insured in Croatia.

In the study, Boromisa also states that low-income and middle-income workers are more vulnerable to the effects and costs of the transition, which includes access to financing for improving the energy efficiency of buildings, as well as rising energy and food bills.

And here we come to the deadly reason – not all workers can protect themselves equally from the heat. Emergency workers will only have incomparably more work during the most extensive disturbances, be it extreme temperatures, floods or landslides.

“When it’s hot”, Schirmbeck further illustrates, “I turn on the air conditioning in my office in the city center, and the builder restoring my facade can’t do it”.

Work safety

The sectors most vulnerable to climate change are water resources, agriculture, forestry, fishing, biodiversity, energy, construction, tourism, health and two cross-sectoral thematic areas: spatial planning and development and risk management. In these sectors, there are significant changes in working conditions, and outdoor workers are especially exposed, Boromisa points out.

Extreme heat is associated with higher mortality, and outdoor workers are most at risk of dehydration, burns and cardiovascular problems. In the US, for example, between 1992 and 2017, heat stress injuries killed 815 US workers and seriously injured more than 70,000 (OSHA).

The American Union of Concerned Scientists also warns that approximately 32 million American outdoor workers “have up to 35 times the risk of dying from heat exposure than the general population”. In addition to outdoor workers, the Center for Disease Control lists people who work in hot conditions, such as firefighters, bakers, farmers, builders, miners, boilermakers, and workers in specific factories as particularly at risk.

That is why it is necessary not only to protect workers from the direct impact of the sun, to provide them with rest and availability of drinks with electrolytes but also to limit the permitted temperatures in the workplace, which the European Union is also considering.

Boromisa points out in the study that employers will have to ensure quality protection at work for their employees.

Jobs disappearing

According to the forecasts of the International Labor Organization (ILO), only due to the rising heat due to climate change, the number of working hours will decrease by 2.2% in the world by 2030, which will lead to the loss of about 80 million jobs, mostly in poor countries. Likewise, the decarbonisation of societies should mean that certain jobs will disappear.

“Current jobs will be gradually extinguished or changed in accordance with changes in technology. In these sectors, a significant proportion of workers will have to acquire new knowledge and skills or face losing their jobs, especially in occupations with an intermediate level of education and skills”, the study states.

What the trade unions must enable in the social dialogue is that jobs are not closed, but that new jobs are created and under fair conditions. Luca Visentini and Ludovic Voet, general secretaries of the World (ITUC) and European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), and SSSH executive secretary for projects, education and European affairs Darko Seperic spoke about this after the presentation of the study.

Setting the conditions for public financing: a decent life for workers and decent jobs

Visentini pointed out that little is said about investing in workers and the social consequences. We need many new jobs, large investments, a protective social network and negotiation. Not much will be achieved without trade unions negotiating positions in institutions from the local to supranational level and in companies.

Voet similarly states that it depends on the trade unions and the organisation of workers whether the discussions about the green transition will be conducted only in the field of company competitiveness, massive profits, business as usual and investment in technologies that reduce the need for jobs, or whether they will insist that workers need a decent life and job.

Both are in favour of conditioning public financing precisely on decent wages and protections for workers.

“The Green Deal creates a lot of new jobs, but there is no obligation for employers to create decent protections for workers or to take on other workers who have lost their jobs due to the climate crisis”, objects Visentini. According to him, progress is impossible without institutions, which are the ones who will say – if you want public money, you need to meet the conditions: how many people will be employed, how many of those will be workers who lost their jobs in decarbonisation, how much will you spend on training, and how much for protection at work.

“If there are no conditions, the workers will be left to fend for themselves”, emphasises the general secretary of the ITUC. He calls for the organisation of workers in both the traditional and green and new, digital sectors, because if they do not start negotiations, they will ultimately be at a loss.

Fund for a rightful transition?

Capital will use everything that enables it to make a profit, asserted Seperic, reminding that child labour was also legal until employers were forced to abolish it.

“We cannot expect employers to do something if they are not given a framework”, he said. He further explains that employers don’t like the responsibility and cost of retraining, but that’s why it’s possible that strict rules go along with technology grants. Although there are European funds to help companies and workers more easily overcome the shutdown of industries with large emissions, Seperic also suggests that the costs of the transition can be financed through its own, national fund, which would be filled with excise duties on fuel.

“Wouldn’t it be logical that part of the excise tax goes to this fund, instead of building new highways that will only make us drive more?”, he asked.

According to him, the most important thing is to demand from the government more ambitious measures towards employers, to recognise which jobs and people are at risk in time and to create solutions accordingly.

Specificities of Croatia

As Boromisa points out in the study, Croatia also has its own problems, in addition to the large damages expected in tourism, food production and other sectors mentioned. In addition to the climate making it difficult for workers to perform their jobs, the rural-urban divide and the division between regions are intensifying.

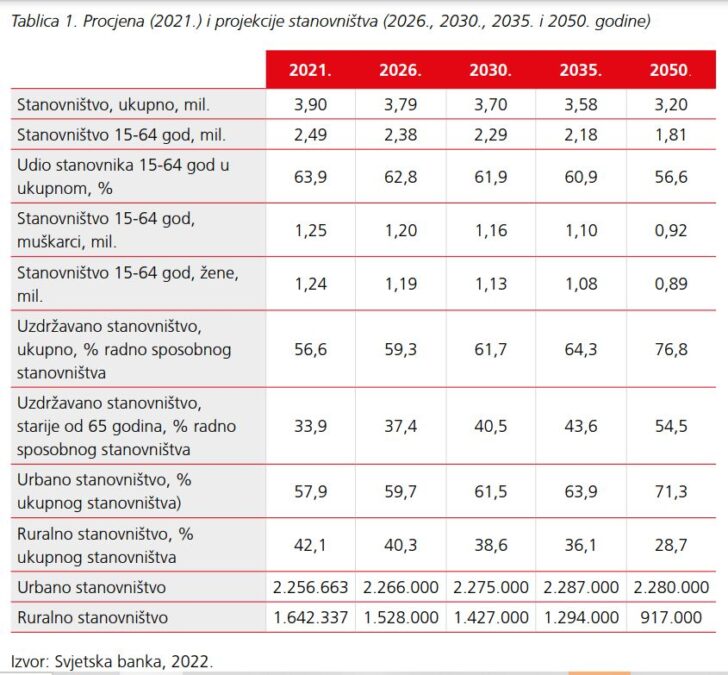

And according to the projections of the World Bank, in the next few decades, the number of the working-age population in Croatia will drop noticeably. By 2050, the population of Croatia will decrease by 11%, and the working-age population by 17%, that is, the share of the working-age population will drop from 63.9 to 56.6 percent.

This opens up a series of questions – how many workers there will be, what they will do and under what conditions; who will regulate and who will pay and how much, for example, the consequences of heatstrokes.

Accepting migration without degrading working conditions

According to a report by climate reporter Somini Sengupta, in a moderate climate scenario, the global south could suffer from annual one hundred to two hundred days of temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius.

This could destroy yields in agriculture and disrupt mining for minerals that are crucial in producing devices for harnessing renewable energy sources. As the climate destroys millions of jobs and makes parts of the world uninhabitable, it will undoubtedly trigger migration.

Boromisa states that migration is necessary, even though workers and jobs are already at risk due to exposure to high temperatures, loss of working hours, the disappearance of traditional jobs during the green transition and the need for retraining.

According to Voet (ETUC), the challenge of the coming time is to accept workers from other countries without degrading working conditions at home. Employers are increasingly open to immigration, but the jobs they provide are poor.

There are no jobs on a dead planet

However, in the case of Croatia, Voet also sees an opportunity to reindustrialise the country in a green way and through EU funds. Energy investments, from thermal to solar, as well as in transport, would create jobs and tangible progress.

“Croatia no longer has mines and heavy industry, you will not have many workers on the street. You are much more affected by the phrase that there are no jobs on a dead planet”, Voet concluded.

Mladen Novosel, president of SSSH, also used this phrase at the beginning of the meeting. The role of this study was to simultaneously involve workers and unions in encouraging the green economy and saving the planet while making these changes socially righteous. Jobs lost in the transition must not be irretrievably lost but intended for society’s new needs, as pointed out at the meeting.

“Hundreds of other problems bother us every day, job losses and low wages”, he said, “but if we don’t have this planet, we have no alternatives. We can only dream about Mars”.