Original article (in Croatian) was published on 21/05/2023

The fact that extreme weather conditions are becoming more and more frequent and extreme causes fear and concern for many.

The uncertainty of the world sliding into a climate crisis, the palpability of climate changes that will be even more pronounced in the future, and the inertness of political leaders regarding specific climate actions are causing strong emotional reactions in more and more people and affecting their making of important life decisions.

The topic of adaptation to the consequences of global warming is no longer a topic that occupied scientists and green activists, that is, only the general public – these consequences have now begun to affect specific local communities. For example, on mussel farmers in the Novigradsko More, where mass mortality of this species was recently recorded, a disease that scientists say has been increasing recently precisely because of the change in environmental conditions and the warming of the sea. Or an olive grove in dry summer Dalmatia, which is particularly vulnerable during those months due to fires.

The fact that extreme weather conditions are becoming more and more frequent and extreme causes fear and concern for many.

What is climate or environmental anxiety?

Modern psychology has described such and similar feelings with the term climate or environmental anxiety.

The American Psychological Association calls eco-anxiety a “chronic fear of environmental destruction” that can manifest in a range from mild stress to clinical disorders such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and coping strategies such as substance abuse. More and more young people are facing such emotions.

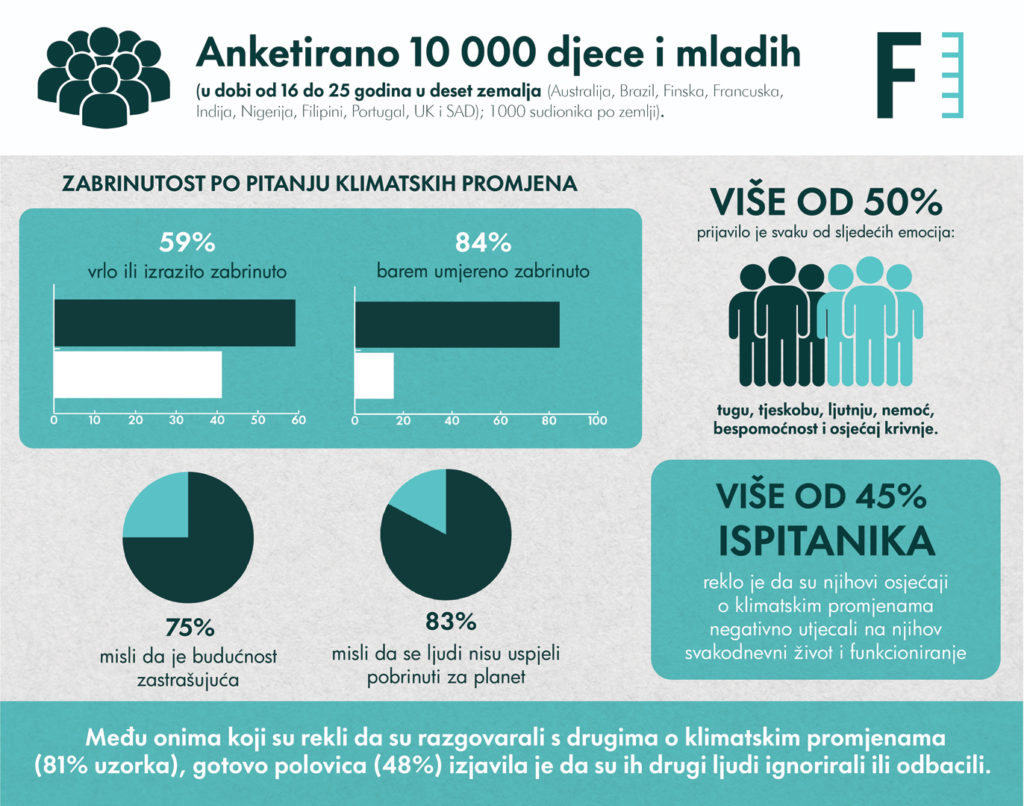

The first major study that gave a deeper insight into how young people feel about climate change was the one published in 2021 in the journal The Lancet and which included 10,000 young people from 10 countries aged 16 to 25.

Illustration: Faktograf.hr

In almost all countries, research participants were concerned about climate change – 84 percent of them, and 59 percent were very or extremely concerned. Almost half of the respondents said their feelings about climate change had a negative impact on their daily lives, 75 percent said they thought the future was scary, and 83 percent felt humans had failed to take care of the planet. At the same time, they rated negatively the government’s reactions to climate change.

Numerous studies, such as the one published last year by the British organization Save the Children, which showed that 70 percent of young people between the ages of 12 and 18 are worried about the world they will inherit, confirm that this topic is important to young people.

These are the reasons why many young people have joined the climate movements, which are becoming more and more present and louder on a global level.

One of them is 20-year-old Mia Bradic from Solin, an ambassador of the feminist organization WAVE (Woman against violence in Europe) and one of the members of the climate movement Fridays for Future. She says that she accidentally discovered the topic of climate change through social networks and independent research on the Internet.

“That’s when I started to understand the magnitude and seriousness of the problem of the climate crisis, it was in the first period of high school. Before that, I was exposed to the topic of environmental protection through education, but we didn’t talk about climate change, especially not in a way that would show the extent of the problem. It was all a bit of a shock because I didn’t understand how it hadn’t been talked about until recently. We, as young people who will feel the consequences of the climate crisis did not have access to the knowledge to be able to face this crisis in the first place”, she says.

In the meantime, she began to study the consequences of climate change, and one of the motivators was the fact that the Mediterranean already feels greater consequences compared to some other areas.

“I am also motivated by the fact that the climate crisis, if it does not already affect all people, will do so in the future”, adds Bradic.

Action – inertia

The connection of the individual with nature is the focus of ecopsychology, which appeared in the nineties as a special response to environmental problems and which starts from the opinion that modern lives are so separated from nature that we simply do not care enough about its protection, which is why we fail to understand the harm that threatens the natural world.

Ecopsychology considers this connection as a precondition that would encourage people to act out of love, not just out of fear.

Marina Stambuk, assistant professor in the scientific field of psychology at the Faculty of Agriculture in Zagreb, explains why climate change makes some people anxious, others into action, and others into inertia.

“People must first believe that climate change is real, that it is caused by human behaviour and that it has negative consequences in order to be activated to take action”, she answers.

However, some people have difficulty assessing exactly how much of a threat climate change will pose. As Stambuk explains, people evaluate certain risks throughout their lives, and we are better at evaluating those risks that have short-term consequences. Therefore, environmental risk is more difficult to define.

“In the case of environmental risk, the consequences appear as a combination of the actions of a very large number of people and they are distant in time and geographically. What we do in the Western world is very well felt by people in poor countries. Poor people are more affected by the consequences of climate change. For example, a farmer from Africa feels more climate effects than a person of middle status in America or Western Europe, and the behaviour of that person from America or Europe contributes more to climate change than that of farmers from Africa”, she says, adding that human behaviour is driven by different goals and values.

When we make decisions about our behaviour, we weigh the advantages and disadvantages and look at the cost that this behaviour will have on us, on our image towards ourselves and towards the world.

“Research shows that when people are asked how they should behave, they mostly give socially desirable answers. Experiments, on the other hand, show that they will behave in a climate-responsible manner if they think that others expect it from them and if they think that others are behaving that way. What is normative behaviour is very important to us”, says Stambuk.

The influence of climate on life decisions

An international study published in The Lancet also shows that 39 percent of respondents said they hesitate to have children because of the climate crisis. Negative thoughts, concerns about climate change, and the impact on functioning in normal life were positively correlated with feelings of betrayal and negative beliefs about the government’s response to climate change in the study.

Stanford researcher Britt Wray, who worked on the study and later wrote the book Generation Dread, said in one of the interviews that we face great challenges because our culture is not emotionally intelligent and it is not easy for us to admit our emotions. Because of this, we try to turn away from things that make us feel uncomfortable, which is not a sustainable way to connect with emotions.

We asked Stambuk if the decision not to have children, due to insecurity and fear of the negative consequences of global warming, is some kind of defence mechanism.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a defence mechanism because that term has negative connotations, but a coping mechanism with uncertainty. Older generations did not grow up with such an awareness of this issue. For example, we would be told that we have to save water while brushing our teeth, don’t throw garbage on the street but in the bin, and we can say that this was some kind of our upbringing, more precisely, an outreach in that ecological upbringing. Younger generations are growing up with a much greater sense of awareness, with the media not helping too much”, she says.

She notes that, on the one hand, the media is important because it conveys information, but at the same time, they are also unconstructive because it mostly conveys information in a fatalistic way, one that increases the feeling of panic. Bradic agrees with such a thing.

“It is very easy to get the impression that it is all or nothing through narratives that represent the climate crisis, in the sense that we will completely manage to keep warming below 1.5 degrees, or we are doomed and there is no way out. “Climate organizations sometimes unwittingly propagate pessimism, which often forces people into inertia because they feel that they are too small for the size of the crisis and the size of the problem”, she says.

Stambuk adds that the issue is large and complex and that young people do not have many sources around them that will model coherent and constructive behaviour. In this context, the decision not to have children is one of the solutions.

“In addition, young people have no hope for themselves that they will see old age in a better world. I would say that it is some kind of response to the current situation”, she says.

Pessimism

We asked the psychologist if the awareness of a problem also increases the feeling of individual responsibility for taking action, to solve that same problem.

“When research is done, it is done on a one-time exposure. If you are exposed to material about climate change, your awareness of the issue grows and the next step is to be more engaged. However, there is some kind of threshold, the point after which people begin to feel helpless and then go into resignation, neglect, suppressing the topic because it is too much for them”, says Stambuk, adding that people often ignore a problem that is complex and that they cannot fully “grasp”.

Activist Bradic says that she can understand people whose thoughts go in the following direction: “Why should I deal with something if there is a bigger systemic problem?”

“However, I try to think from a collective perspective and suggest that people try to influence the structures they are surrounded by. I encourage people to – instead of worrying about the plastic bag they might have bought – join collectives in their local community or start a collective of their own and try to influence the decisions of local governments. Changes at these levels will result in larger systemic changes that will enable us to stay within that key temperature limit of 1.5 degrees”, she says.

Croats and the climate

The question, however, is how interested the young people in Croatia, as well as the general population, are in the issue of climate change.

Part of the answer to that question is provided by the report “The lost decade: Attitudes and opinions on environmental protection, climate change and energy transition in the Republic of Croatia” published in 2021 by the Society for the Design of Sustainable Development (DOOR), which was created based on research by the Institute for social research in Zagreb. The same attitudes were investigated ten years earlier.

Croats, namely, do not see the topic of the environment as important in comparison to some other topics, but for most, the topics of economy, poverty and health are more important.

This, as the authors of the report point out, says two things: that the trend of neglecting environmental issues in public space is confirmed in Croatia, and that there is insufficient knowledge and linking of cause and effect links between natural resources as an economic basis and successful socio-economic development.

Likewise, there is significant information indicating that the Croatian public still holds the opinion that climate change is equally caused by natural processes, even though scientists agree that the recent warming is the result of human influence.

“This is the defeat of our system of science, education, research, but also the communication thereof and in a way a ‘victory of the flat earthers’ and indicates the absence of an adequate level of understanding of the causes and harmful consequences of climate change that would be in line with scientific understanding”, the report says.

We asked Mia Bradic if she notices that people of her generation share the same concern about climate issues. She says that interest in this topic has grown among young people in the last five or six years, partly due to the greater visibility of the climate movement and young people in climate movements on a global level.

“I rarely meet young people who deny that global warming exists”, says the young activist, adding that Croatia urgently needs a comprehensive education plan on climate change as part of the school system.

People are looking for answers

Although climate anxiety is not officially recognized as a mental health condition or disorder in diagnostic manuals, it is nevertheless a condition that is on the rise, which is why there are already therapists who specialize in these topics.

A sufficiently strong indicator that the topic of climate change on a global level has begun to worry people is the number of searches on the Google search engine. According to data obtained by the web portal Grist, searches for the term “climate anxiety” increased by 565 percent in 2021 compared to the year before.

Simon Rogers, Google News Lab’s data editor, says he’s seeing changes in what people are searching for regarding climate change. They are increasingly trying to come to grips with what the crisis means for their lives and are looking for answers. For example, in the week when the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was released, many media outlets warned about the problem with alarming headlines, and the BBC then warned that it was a red alert for humanity. Searching “what can I do about climate change?” that week increased 27 times compared to the average and reached an all-time high.

Coping mechanisms

“Our anxiety is not related to future scenarios, but to things that have already happened”, says Mia Bradic who adds that more and more people are talking not only about anxiety but about climate emotions in general.

The young activist participated in the previous climate conference COP-26, which took place in Glasgow. She says that the climate crisis puts people in front of a key moment in the history of modern societies, which is to start thinking about our relationship with production and the planet, about the relationship we have with each other and about social values.

The period of adaptation to the climate crisis represents an excellent opportunity to deal with other social problems such as gender inequality, exclusion of people with disabilities, and racial discrimination. “What helps me deal with this anxiety better is an action for systemic changes”, she says.

Other recommendations refer to taking care of physical health, limiting exposure to climate-related content, going out into nature, and connecting with like-minded people.

Anxiety as an unpleasant psychological state, Stambuk says, can have several sources. As the topic of climate change gains more and more importance in the public sphere, it becomes a source of anxiety for more people. Her recommendation is for people who feel such emotions to determine what is under their control and what is not.

“We can do this by drawing a circle and inside the circle we write down the things we can influence. These things should be dealt with. We can deal with the fact that our daily habits can reduce the carbon footprint, how to spread this idea in some of our circles, join groups that deal with it, organize actions. It’s a kind of general path, and, of course, each of us can judge for himself what suits him best”, Stambuk said.