Original article (in Serbian) was published on 01/08/2023; Authors: Stefan Janjić, Ivan Subotić

The editorial office of FakeNews Tragac received a report regarding the comment “The grain deal is meaningless”, written for Politika by Aleksandar Bocan-Harchenko, the ambassador of the Russian Federation in Serbia. Among other things, he states the following:

- that the agreement does not ensure food security at all, but rather “fills wallets and perpetrates terrorist attacks”;

- that “the lion’s share of the burden” is sent to countries with the highest level of income;

- that not even three percent of Ukrainian exports go to the least developed countries;

- that none of the provisions stipulated in the Russia-UN Memorandum on the normalization of Russian exports of agricultural products and fertilizers have been implemented.

We searched the available data of the United Nations (on which Bocan-Harchenko relies), reviewed contracts and secondary sources, and finally sent a question to the ambassador of Ukraine in Serbia, Volodymyr Tolkach, regarding the export of grain to the most vulnerable countries.

What is foreseen in the agreement?

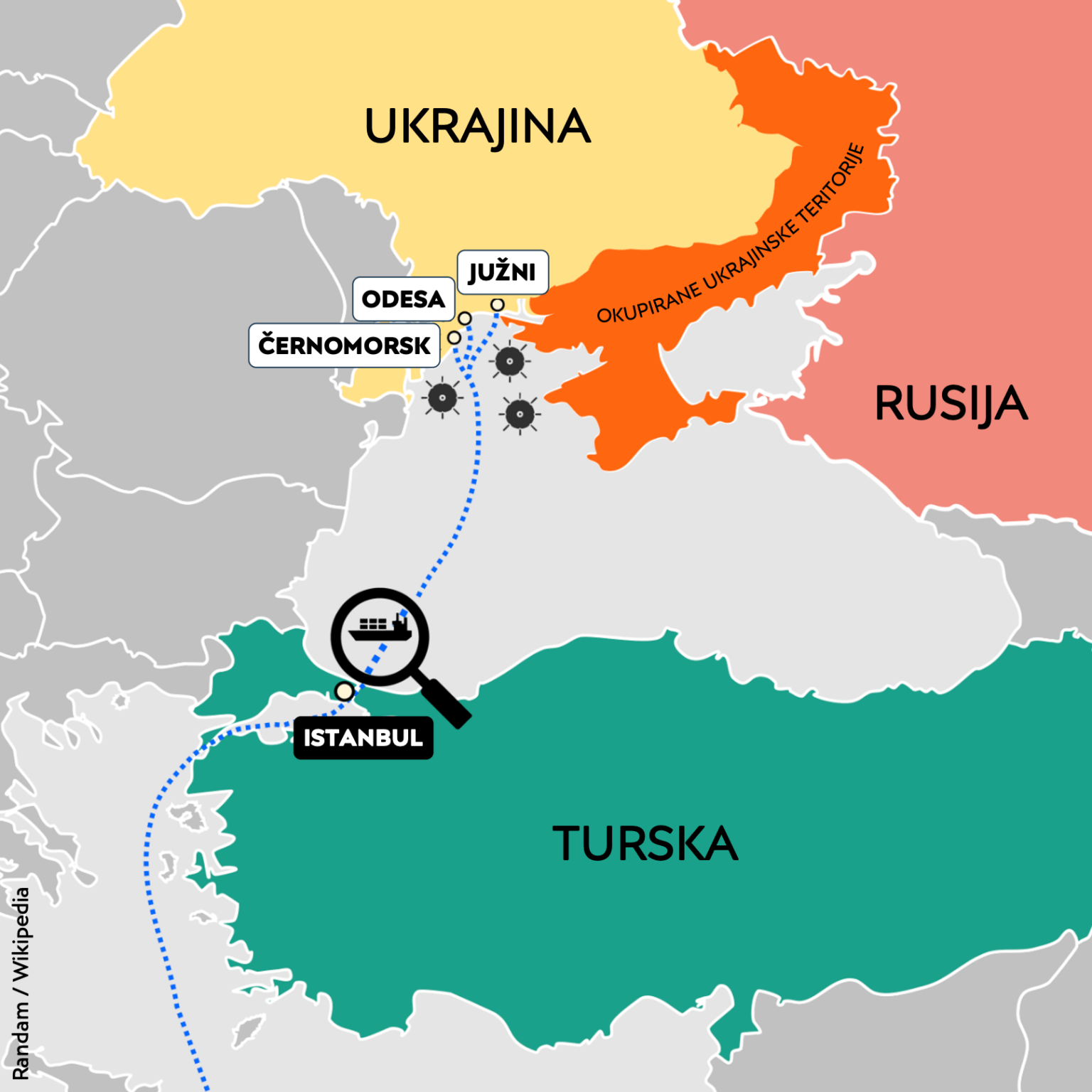

The Black Sea Grain Deal, signed last July in Istanbul, guaranteed the safe transport of Ukrainian grains and fertilizers across the Black Sea in wartime conditions. Russia has pledged not to block or target cargo ships, and teams to inspect ships and cargo have been set up in Turkey. The text of the initiative is very concise and refers to the technical aspects of overseas traffic: there is no reference to the wider context, the war is not even mentioned, and there are no provisions on export quotas.

Along with the aforementioned agreement, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the Russian Federation and the United Nations Secretariat. Although neither war nor sanctions are explicitly mentioned in it, it is clear that the agreement aims to mitigate the consequences of sanctions against Russia within the framework that would facilitate the export of food and fertilizers, including ammonia.

The goal of the initiative is to mitigate the consequences of the food crisis, which was largely caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the introduction of sanctions against Russia. Since Ukraine and Russia are extremely important producers and exporters of food in the global framework, the war led to major problems with supply and price growth, which especially affected the poor countries of Africa and Asia.

In what respect is the Russian ambassador right?

In the beginning, it should be pointed out that in the text, Bocan-Kharchenko relies on United Nations data on Ukrainian exports within the framework of the Black Sea Grain Deal. Although the ambassador nowhere mentions the UN as a source, the numbers match what can be seen in a systematic and interactive review on the United Nations website.

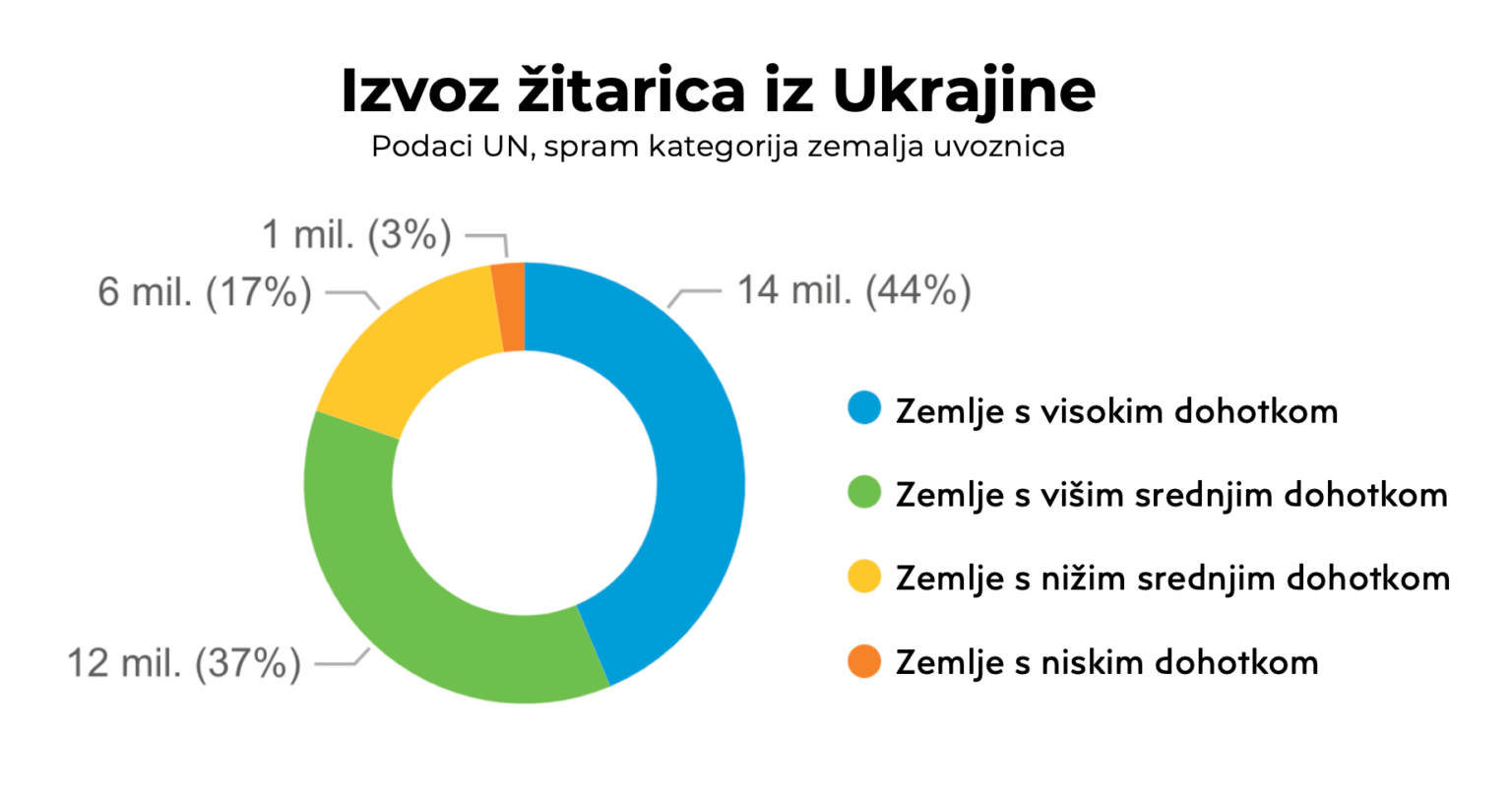

The website sorts the data according to the importing countries, the number of imports and the types of grain. Overall, most of the exports ended up in China, Spain and Turkey. Out of a total of 32.9 million tons, 26.4 million ended up in high-income countries (such as Spain, Italy, the Netherlands…) and upper-middle-income countries (China, Turkey, Libya…). The numbers cited by the ambassador in this sense differ slightly from the UN data.

Furthermore, 822,000 tons were directly exported to low-income countries, which is about 2.5% of Ukrainian exports realized based on the Black Sea Grain Deal. This way the grains reached Ethiopia, Yemen, Sudan, Afghanistan and Somalia.

So, if we look at the distribution of Ukrainian grain exports to primary importers, it is true that the vast majority was exported to countries with high and upper-middle income, and that less than 3% of the cargo was exported to low-income countries. However, does this mean that the agreement is meaningless and that it “does not ensure food security at all”? No, such an interpretation would be very narrow and manipulative.

In what respect is the Russian ambassador wrong?

Poor countries, which are at risk of starvation, do not function as economic “islands”, cut off from the rest of the world. The prices of raw materials and the quantities of food products that reach these countries depend to a large extent on global supply and prices. As stated by the United Nations in a report published on June 30 this year, food prices at the global level fell by 22% compared to March 2022, which was largely contributed to by the Black Sea Deal. Such circumstances have relaxed the position of not only the poorest countries but also the poor sections of the population from lower-middle-income countries (Bangladesh, Iran, Djibouti…).

The same report shows that the proportion of Ukrainian grain exports to the least developed countries and sub-Saharan African countries remained almost the same compared to the period before the invasion.

It should also be noted that the statistics we talk about all the time are actually based on groups defined by the World Bank, where – for example – Bulgaria, Serbia, Turkey, Gabon, Iraq and Turkmenistan belong to the same (second most powerful) category, while Ukraine is in the third category, along with Tanzania, Bangladesh, Ghana and Nigeria. Although some form of grouping is necessary, there are crucial differences between countries in the same categories.

The importance of the agreement is also confirmed by the OUN Conference on Trade and Development in its report from October 2022. Let’s take Bangladesh for example. In 2021, before the start of the war, this country imported 578,000 tons of grain from Ukraine. After the beginning of the invasion, the import was completely stopped and only the Black Sea Deal enabled the continuation of the supply (210,000 tons in 2022).

What does the Ukrainian ambassador say?

The comment of the Russian ambassador was initiated, as he states, by the announcement of the conference of the Embassy of Ukraine in connection with this topic. The conference was held yesterday, in Belgrade’s Media Center, and it was an opportunity to ask Ukrainian ambassador Volodymyr Tolkach a question regarding the different interpretations of UN data.

In his address, Tolkach said, among other things, that Russia uses food as a weapon and blackmail, and that it did not stop only at exiting the agreement, but “launched rockets and drones at Ukrainian Odesa, where there are three ports for grain export”. The Ukrainian ambassador states that “the terrorist actions of Russia in just one day led to an additional increase in food prices on the global market”.

Since Tolkach presented the information that “65% of Ukrainian grain exports are sent to the most threatened countries in the world”, we were interested to know what he based this estimate on.

In his reply to Tragac, Tolkach stated the following: “When the war started, Ukraine found itself in a situation where it had to solve many issues at once: who will insure these ships, who will guarantee security, how will the grain reach the final destination… Many countries in Europe have offered to act as mediators in these affairs”. He then reiterated that he stands by the conclusion about 65% of exports to vulnerable countries, as well as the thesis that some European partners have taken over the distribution tasks that Ukraine dealt with before the war.

At the moment, however, there are no comprehensive data based on which we could calculate the ranges and directions of redistribution. Also, there is no summarized data on the consequences of the difficult export of Russian products and fertilizers.

Towards conclusions

At the Russia-Africa Summit, held last week in St. Petersburg, representatives of 17 African countries appeared (in 2019, at the first summit, there were 43). Several leaders, including Azali Assumani, the president of the African Union, emphasized that the Grain Deal is of vital importance to the continent and that it is necessary to find a model for its renewal.

Russian President Vladimir Putin presented arguments similar to those we could read in the text of the Russian ambassador to Serbia. He promised, at the same time, free 25,000-50,000 tons of grain to Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe, Mali, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Eritrea. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said that this kind of donation to individual countries cannot fix the dramatic consequences of leaving the agreement.

In his text on the food crisis, Ambassador Bocan-Kharchenko does not question the responsibility of Russia in any segment, which, by invading neighbouring Ukraine, made the transportation of Ukrainian grains dramatically more difficult. Last year, less than a day after the signing of the agreement, it targeted the port of Odesa. In such an atmosphere of uncertainty and risk, even the agreement was not a guarantee that the transport would be carried out smoothly. Although Bocan-Kharchenko calls the agreement “nonsensical”, referring to the low level of direct delivery to the poorest countries, the representatives of these very countries announced in St. Petersburg how important this agreement is to them.

Note: (1) Demostat also dealt with this topic in its text yesterday; (2) Quotations from Ukrainian Ambassador Volodymyr Tolkach are given in accordance with the Serbian translation provided at the conference in the Media Center. The ambassador addressed the journalists in Ukrainian.