Original article (in Serbian) was published on 13/09/2023; Author: Marija Vučić

Of the thousands of products on the shelves, twenty of them have temporarily become cheaper as of today. Ever since President Aleksandar Vucic announced this pompously at a press conference to which he brought a basket from the supermarket, the pro-regime media has continued to “enhance” the story about the measures the state is supposedly using to save citizens from economic misery. However, they do not mention that inflation in Serbia is among the highest in Europe, that the average salary is not enough for the consumer basket, that pensioners live on the brink of existence and that populist government measures in the form of one-off benefits and extraordinary increases in pensions will bring even more debt, price increases and an additional drop in standards.

These days, Minister Sinisa Mali is visiting TV studios from RTS to Pink and presenting the measures previously announced by Vucic, and his statements are further shared, without any critical review, by pro-regime web portals and newspapers.

Thus, for example, Vecernje Novosti, like the Government’s PR service, reported the minister’s words about how inflation is slowing down, how the state is implementing effective measures such as aid of 10,000 dinars for children under 16, how food prices are under control, how Serbia is a financially stable country.

Informer, Alo, Republika have similar praise for the measures announced by Mali and Vucic.

However, if you are an average citizen of Serbia, it is immediately clear to you that this is propaganda because you are most likely living worse than, say, last year at this time. And this is confirmed by the official statistics.

Are prices falling down? No.

The fact that 20 items will temporarily become cheaper does not mean that prices will generally fall down. On the contrary. Official data from the National Bank of Serbia show that prices in August this year were 11.5 percent higher than last August.

The Ministry of Commerce cross-checks data on average prices with average wages – the statistics they get show unequivocally that purchasing power is declining. For example, last June, you could buy 701 litres of cow’s milk for an average salary. In June of this year, you could buy 135 litres less. Last year, you could buy more than 4,000 chicken eggs, and now you can buy a little more than 3,800. Some products are more available, such as oil or flour whose prices were frozen by the state.

If the prices are compared with those of previous years, the differences are even more dramatic. For example, the Cenoteka website notes that in 2018, a 125-gram pack of butter cost about 170 dinars. Today, the same package costs more than 300 dinars.

In September 2020, one package of T-500 flour cost an average of 58 dinars. These days, the same flour costs about 80 dinars.

This general increase in prices is called inflation, and the good news is that the inflation rate – that is, the rate of price increase – is decreasing, after reaching a peak of 16.2 percent in March of this year.

However, a drop in the inflation rate is not the same as a drop in prices, says economist Goran Radosavljevic. These statistics only show that prices are still rising, just more slowly.

“I was driving at 120, now I’m driving at 100 – I’ve slowed down, but I’m still driving fast”, he explains.

We can hope that the prices will slow down to a certain level and then stop there, but we cannot hope that they will fall – we will probably never pay 170 dinars for the aforementioned butter again.

“You can expect to pay it, say, 305 dinars. Since we have been measuring the consumer price index, it has never happened that we have a reduction in price”, he says.

This economist draws attention to one important fact – the fact that the general inflation rate is 11.5 percent does not mean that the price increase is the same for everyone.

Namely, the average consumer baskets of the poor and the rich are not the same – citizens who earn below average or live on the edge of existence, as a rule, spend the most on food per month, explains Radosavljevic.

And it was food that became more expensive – statisticians calculated that in August, food and soft drinks were 16.9 percent more expensive than in August last year. However, there is a difference, says this economist, between statistical inflation and the subjective feeling of inflation.

“If food is half of your basket, it means that the inflation for you is not 11.5 percent, but, for example, 47 percent”, he says.

Therefore, since the largest number of Serbian citizens earn a salary lower than the average, data on food price growth are more relevant than general price growth. Namely, they also include items that the majority of the population cannot afford – there are the prices of cars, computer equipment, travel, meals in restaurants, cosmetic or hairdressing services, etc.

Wages and pensions are growing, but so is the price of the consumer basket

Mali also boasted about the increase in salaries and pensions, which Vecernje Novosti shared instead of putting the numbers he presented in a precise context.

“In June, the average salary was 726 euros. Compared to June last year, that salary is 1.2 percent higher in real terms”, said Mali.

This is true, but there is a “catch” here as well.

The average net salary (the salary that remains when taxes and contributions are paid from the total, gross salary) in June amounted to 85,539 dinars, which is a real increase of 1.2 percent compared to last June.

However, salary amounts fluctuate slightly from month to month – so salaries in June this year were less than those in May 2023.

What does this “thin” and current year-on-year increase even mean to a citizen who, for example, receives an average salary of around 85,000 dinars? Practically nothing – in the previous 15 years since the statistics of the Ministry of Trade existed, the average salary in Serbia was never enough to cover the average consumer basket.

This trend continued this year as well (the latest Ministry statistics are from June 2023).

So, if you received 85,539 dinars in June, you still lacked about 15,000 dinars to afford an average consumer basket that month.

It also depends on where you live. Only in Belgrade, where the average salary was about 108,000 dinars, you could cover the average consumer basket and still have about 5,000 dinars left over, judging by the statistics. In Leskovac, even though the basket is cheaper there, you need a salary and a half.

“One percent of real growth is essentially nothing. The problem is that it is also a statistical average. For those who earn below that average, which is 70 percent of the population, that growth is realistically lower because their inflation is higher”, explains Goran Radosavljevic.

It should also be noted that the average salary is not a precise indicator of standards.

Let’s imagine, for example, that there are only four people in the company – one earns 200,000 dinars, and three of them earn 40,000: statistics will say that the average salary of that company is 80,000 dinars.

That is why the so-called median income shows a somewhat more realistic situation – the maximum amount that 50 percent of the population earns. For example, if we were to make a large table of all the employed and engaged in work in Serbia, as well as their wages, the amount earned by a person exactly in the middle of the table would be the median salary. In this way, a more accurate picture of the standards is obtained, because as a rule, a small percentage of richer citizens whose high earnings “pump up” the average are exempt.

Media net earnings in June amounted to slightly more than 65,000 dinars. That is, therefore, the amount that half of the citizens of Serbia earn, or less than that. For them, one salary was definitely not enough for the average consumer basket – which cost around 100,000 dinars in June.

Radosavljevic notes that median net earnings can also be “calculated” and that it is not an absolute indicator of the situation, but it is more relevant than the average salary.

“Therefore, we should observe both indicators and keep in mind that there are more people who have a median salary and less than an average salary and more”, he says and adds that 70 percent of people in Serbia do not earn a statistically average salary.

But that’s why, according to data from 2021, a fifth of employees are on the minimum wage. According to this economist, as much as 80 percent of their earnings go to food.

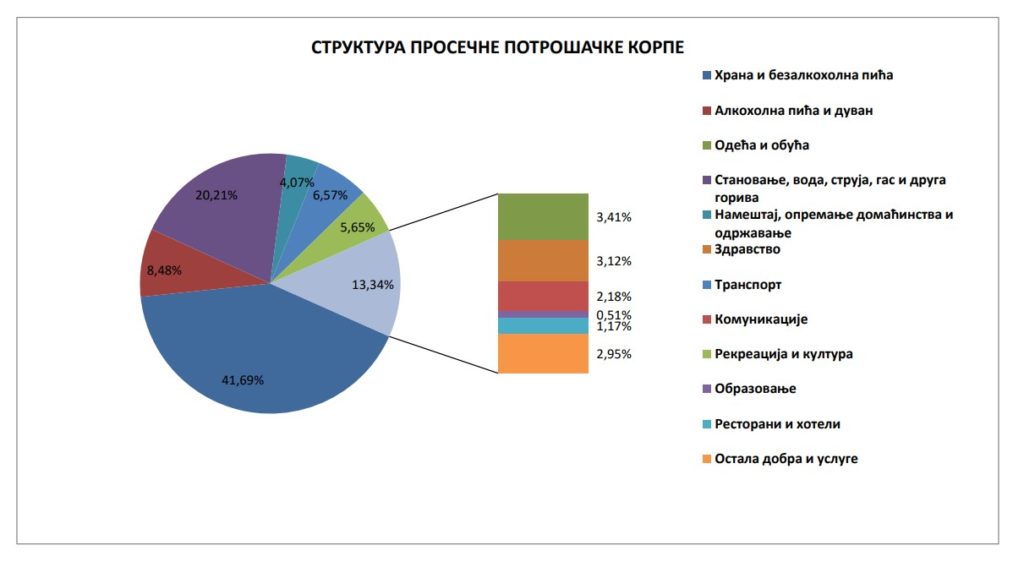

The average consumer basket, by the way, includes the expenses necessary for the normal functioning of a three-person household during the month – this is the amount spent on food, drinks, bills, transportation, alcohol, cigarettes, etc.

Benefits are more expensive than measures

Mali also boasted about taking care of pensioners through increasing pensions and one-off benefits, and Vecernje novosti also reported this.

And that’s true – data from the PIO fund show that, compared to June last year, the average pensioner this summer had about 7,000 dinars more in pension. Nevertheless, it amounted to about 37,800 dinars on average, which is on the very edge of existence – not enough even for the minimum consumer basket.

These days, the government announced two more extraordinary increases – from 5.5 percent starting in October, and from January next year by as much as 14.6 percent.

What the pro-regime media does not convey, however, is that these increases can cause long-term problems for citizens, as assessed by the Fiscal Council, the state body in charge of evaluating the state’s fiscal policy.

As an example, they cite the increase in pensions during the 2008 economic crisis, which even collapsed public finances. Namely, the key prerequisite for increasing pensions is a stable economy that will be able to finance it – that was not the case then, so in the end those same pensioners suffered the consequences.

“In the years that followed, pensions were therefore temporarily reduced, they had periods of freezing and slow increases, until their amount finally returned to an economically sustainable level”, reveals the Fiscal Council.

The same is the case, according to the report, with indiscriminate cash payments that the pro-regime media mention in a positive light. For the payment of 10,000 dinars for each child up to 16 years of age, 100 million euros will be allocated. Handing out money to everyone based on age, and not on the criterion of social vulnerability, is a bad social policy that also has its economic consequences, according to this institution.

“It should also be borne in mind that, due to the payment of such economically and socially unjustified forms of financial support, the citizens of Serbia are already in debt for around 2 billion euros from 2020, at very high-interest rates”, states the Fiscal Council.

How will these benefits be financed? Logically – through additional borrowing but also an increase in tax levies, as stated by the Fiscal Council. The state has announced an increase in excise duties on petroleum products, coffee, tobacco and alcohol, and these price increases, experts from this institution point out, will lead to further inflation, i.e. a rise in prices and a drop in citizens’ standards.

At the European top

The latest data from the European statistics agency Eurostat, as well as from local central banks and statistical institutes, show that Serbia was at the top of Europe in July of this year, with a price growth rate of 12.5 percent.

Ahead of us that month was only Turkey with galloping inflation of 47.8 percent and Hungary with 17.5. Even in Ukraine, where the war has been raging for a year and a half, prices rose somewhat more slowly – the inflation rate was 11.3 percent.

At the level of the European Union as a whole, the price growth rate in July was 6.1 percent, and the lowest rates were in Belgium (1.7 percent), Luxembourg (2 percent) and Spain (2.1 percent). In the eurozone (a territory narrower than the EU where the euro is used), inflation is also lower – 5.3 percent. The prices of services and food rose the most.